Feature

This collection highlights my work as a journalist, primarily with Gulf News (2003–2013) as a writer, multimedia reporter, and subeditor across both magazine and newspaper formats.

My journalism career was built on a foundation of in-depth research and narratives that capture the essence of people, events, and ideas shaping our world. With hundreds of bylined articles ranging from long-form features and first-person pieces to cultural deep dives and human-interest stories, my editorial work reflects both journalistic integrity and the art of storytelling.

Each article in this portfolio is a testament to my ability to translate complex subjects into engaging, accessible narratives whether covering social issues, industry trends, or personal journeys that deserve to be told.

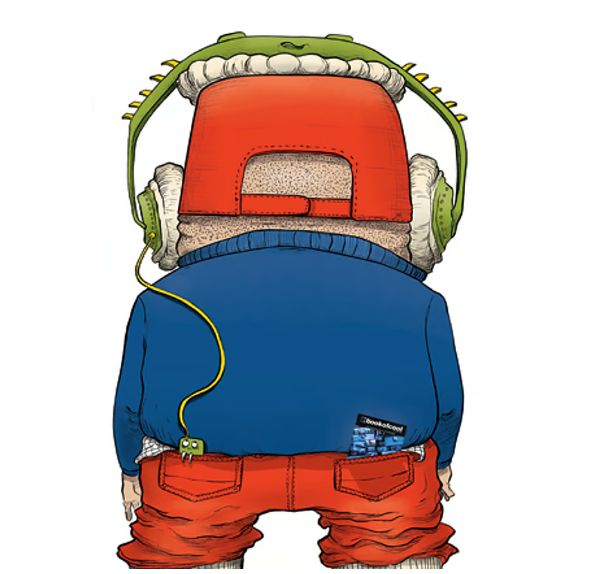

The Code of Cool

Is ‘cool’ a code that can be cracked?

If famous British novelist Martin Amis didn’t scruple to use the word ‘uncool’ during an interview with The Times, surely we shouldn’t feel guilty about using ‘cool’ – the opposite of uncool.

Despite his authoritative lexicon, Amis picked, er, such a commonplace word to contextualise his age (60) and the fact that he is a grandfather, calling toddlers “a telegram from a funeral parlour”.

We are guilty too. You, me – everybody.

‘Of what,’ do I hear you ask? Of allowing the word ‘cool’ to creep into or gatecrash our everyday lives. We use – and abuse – this one-word label to identify people, things, places and feelings. Shaking your head from side-to-side, are you? C’mon. You ought to be nodding your head up and down, admitting that you fall prey to phrases like ‘that’s cool’, ‘pretty cool’ or ‘I’m cool with it’.

Or perhaps, in Amis’ vernacular style, you ‘feel uncool’?

Despite its ubiquity the word, surprisingly, does not have a definitive meaning.

All at once, this one-syllable word swallows up simple constructs like attitude, appearance and style as well as complex constructs like state of being. It embodies our social consciousness and ideals with such coercion that we ought to deign its status to that of a poster child – only faceless, but still emblematic.

The word has such occult power that it inspires books too. In the case of Book of Cool, it locks itself in the title as well.

The book, a tutorial with a three-volume DVD set, is about activities that will enable you to master the “cool things that you see in life”, according to the authors Fred Rees and Dominic Sheridan.But they too admit that the word belies definition.

So how are we regular folks to make sense of the word we use to express admiration, approval, and even define our aspiration?

Rolling Stone magazine once referred to cool as allusive and indefinable, and that its meaning is perpetually shifting.

Rees and Sheridan agree, saying that people’s idea of cool is subjective. “If you physically do something that you think is cool, then that defines the concept on an individual level. On a broad spectrum, ‘cool’ is ever-shifting; on a personal level it is definable. If a 100-year-old war veteran believes that being able to reload his rifle in five seconds is cool, who are we to argue? For us,if you have spent time learning how to do an activity, then that is cool. How cool others will find it depends on them.”

Sigh.

Similarly, what if we were to take the liberty to tear down the word ‘cool’? Let’s find out.

In language

First, let’s agree that the word does not have simplistic associations. Unlike, let’s say, dialect. Wouldn’t you agree that it is easy to associate British English with culture, Italian with passion or French with romance?

But cool? The word transcends cultural bias and yet penetrates global language with countless connotations.

The word helps us make sense of our lives, sort out issues, and peanut-pack our awkward reactions. Take the case of Melissa Andrews, a Dubai-based professional. She believes that the word has become a stock reply with universal context. “I use it all the time. I’ll say, ‘I had a cool time’, ‘That person is cool’, ‘I went to a cool place’ or ‘That’s not cool’. I don’t need other adjectives. It is the easy way out.”

By “easy way out” she means the expression helps her communicate quickly and effectively. She says, “If I happen to notice a customer being rude to a waiter in a restaurant, I’ll turn to my friend and say, ‘That wasn’t cool’. I could also use the phrase ‘profoundly disturbing’ or another adjective, but using ‘not cool’ relays the same sentiment.”

Andrews isn’t the only one. Pop stars use ‘cool’ in their songs (Gwen Stefani sings, ‘… After all that we’ve been through/I know we are cool’); magazines use it in their articles (Jane Birkin: How to Look Cool at 63) and authors try to crack the code of cool (The Birth and Death of the Cool by Ted Gioia and In the Know: The Classic Guide to Being Cultured and Cool by Nancy MacDonell).

While it is all tickety-boo that the word cool has showed up in so many places and its versatility has been proved time and again, it is a cause for worry. Our vocabulary is being single-handedly hijacked by one word. Its usage was once restricted to colloquialism – seemingly used first by British novelist and playwright Wilkie Collins in the 1860s. Now, it has found mainstream acceptance in our lingua franca.

Ashfana Hameed, a public relations manager in Dubai, uses the word as a substitute. “I’ll use it instead of ‘yes’ or ‘OK’. I use the word a lot – it is versatile. If a friend asks me whether a particular painting will look good, I’ll reply, ‘It’ll be cool’.”

So, in linguistic terms, cool describes anything worth describing. Moving on.

In age

When Debenhams commissioned a survey earlier this year to find out how the position of a man’s trouser waistband – hoisted above, around or below the waist – provided a clue to a man’s age, it was amusing at the outset and now thought-provoking.

One factor, in this case the position of waistband, was an indicator of a man’s age. (By 45, men tend to wear their trousers 2 inches above the waist and 3 inches higher by 57.)

You’re probably wondering how this information fits in with our attempt to tear down the word cool. Stay with me.

If the level of one’s waistband provides clues to one’s age, could the usage of the word cool – and the extent to which we use it – also provide clues to a person’s age?

People from the younger generation tend to use it a lot more than those who are in their late forties and up, says Andrews.

Try this. The breezy, ‘Cool, go ahead’ (when a friend decides to carry on without you); or the acrimonious ‘I am not cool with that’ (when you disagree with your partner) and placatory ‘Cool it guys’ (when you are defusing a volatile dialogue) – are phrases that may not fit in, depending on your age.

Further validation comes from the authors. Rees and Sheridan say the demographic that gains most from the Book of Cool is aged ten to 18.

“It is also aimed at anybody who wants to watch cool things and learn things that would be fun to do.”

Going by the activities listed in the book – juggling, break-dancing, soccer, pool shots, and so on – the age of a person would determine how much time he can spare to try out the activities. “We guess the younger generation has more time than the older. However, it is up to the individual to find the time to do the things that he wants,” they say.

We come back to the same spot. If cool isn’t strictly restricted to age, then is it to do with an aspiration?

In aspiration

British columnist and writer A.A. Gill wrote, “We learn to like what our peer group likes, and we aspire to admire what the folk we admire admire.”

The fact is, people admire people who they think are cool.

Luke Battley, a Dubai-based project manager, says being cool has become a general aspiration. “I think I am highly uncool. Cool people have a style, an individualistic trait, a set of skills that most others do not.”

If cool is an aspiration, it reflects a larger argument about how deeply we invest in keeping up a façade or building an image.

It may be the case, say Rees and Sheridan. “People obviously invest heavily in building and keeping an image. The Book of Cool isn’t the pretentious cool. A person’s looks can fade or an image can be turned upside down by a mistake or an event, but knowledge cannot be taken away, and is cool.”

In the book, you’ll find “things that look like great fun, but somehow seem out of reach”. The authors claim all you need is the right knowledge and application to do the things you think are cool. “[The book] is full of the most talented people who show and teach you how to do all those brilliant/cool things. Cool means good/fun/desirable, and these are things people want on a basic level.”

In social acceptance

Though Rees and Sheridan think that most would view the Book of Cool as an introduction to learning things that will impress others, they also emphasise that it should be about your own enjoyment. Although they do admit that if you master something, impressing friends “will probably naturally follow”.

In others words, being cool is the paradoxical standing out to fit in.

Take the case of Lucas Metaxas, a grade 12 student at Dubai College. He flipped through the book and found several activities that could make him more popular among his friends.

“Cool means popular. It applies to someone who has many friends and gets invited [out] a lot. Playing sport is cool. I learnt football tricks from the book and my friends said, ‘Wow! Where did you learn to do that?!'”

Or, as Battley puts it, “I want to fit in to avoid standing out.”

Our teardown process: has it helped us identify the constituent parts of the word cool? You be the judge.

But before you go, I’ll take my turn to tell you what I think of cool. In the manner of the SarcMark, the punctuation mark for sarcasm that has a squiggle with a dot inside, the word cool too should have its own emoticon. Cool, eh?

Book of cool

Fred Rees has been working as a commercial and documentary film director for the last 15 years, specialising in sports productions, and is the CEO of Ocelot Productions Ltd, the company that created The Book of Cool. Dominic Sheridan is the resident technical expert.

They share a few interesting facts about their concept:

“We made a list of the type of activities we thought would be good – and cool – to feature, and then tried to find the most talented people.

“When we approached the experts, those who were at the top of their game – world champions and world record holders – immediately got the idea. Though money was part of the arrangement, they were happy to share their knowledge.

“We travelled and filmed people wherever they came from and [wearing] whatever they turned up in for the shoot. The reality of things is cool enough for us.”We created a website because we didn’t have the studio power to acquire the right retail shelf space or the funds to properly advertise our product. Our website won three Webby Retail Awards – the Oscars of the internet.

“The idea came to me [Rees] one day: wouldn’t it be amazing if there was a book that enabled you to master the cool things that you see in life? It wasn’t a deliberate decision to feature more men then women. It was just the way it worked out. We looked for the best people in each activity. We don’t think it matters whether the person teaching is a man or a woman; the insight and the knowledge is important.

Disclaimer

This article was originally published in Gulf News and authored by me. Read the original version here.